Stuck on a project? Get unstuck at a museum!

How do I know I’m stuck?

Like any creative professional, I sometimes find myself stuck on a project. Pushing forward would only yield more of the same. Looking at my normal references, like Pinterest, feels pointless because I am not seeing any new solutions to the problem I’m working on. It’s the point of diminishing returns, when it’s better to put the design work down for a bit. It’s time to go recharge the problem-solving part of the brain.

Why go to a museum?

For me, art museums are a great place to get unstuck, both on a specific solution for a project, and on the larger questions like where my creative career might be going. A museum space is already set-up for long form, concentrated observation and introspection. A museum is one of the few places where you can go alone, walk slowly, stare, and not look crazy. Museums are also (mostly) non-commercial, and block out the normal distractions like “should I get a coffee?” and “Nice shoes - ooh, and they’re on sale!”

The painting in the background is my very rough study of Matisse's 1915 Geraniums that's currently at the Harvard Art Museum. No original oil paintings had anything taped to them to produce this post.

How to use a museum to get unstuck

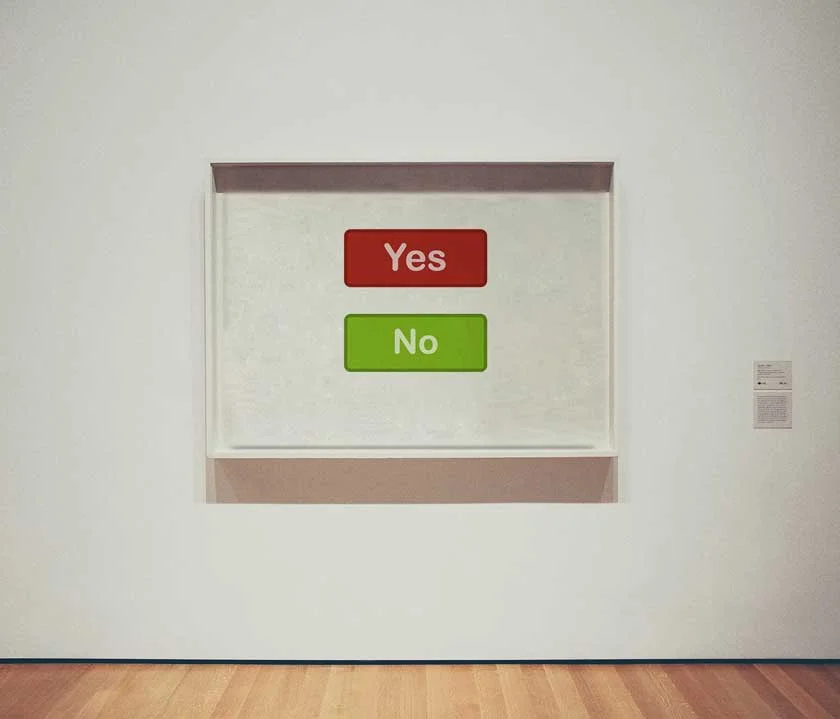

What works for me is pretty simple. First formulate the problem I’m having (for example, a web page layout feels too complex and unbalanced. I’m stuck on how to pull it all together.) Then, ask the question of the art I am seeing. Then, see what happens.

1: Define the problem

To help define the problem, I ask myself a few honest questions. What’s the first thing I don’t feel like touching on this project? Where does my current product not yet measure up to where I’d hoped to have it?

2: Ask the question

Let’s say my problem was with the composition and clarity for a web interface. I would formulate my question about the exhibition as - how does the artist deal with complexity? How are multiple objects balanced so they make sense together?

3: Bring a sketchbook!

Notes, and especially notes with drawings, will help remember any ideas and solutions. I have more sketchbooks than I probably should, and always have at least a tiny Field Notes style book and a pencil in my purse. A smartphone can work for typed notes, but really does not work as well for me when I want to capture things quickly and loosely.

4: Take notes and summarize

I always find that the better I had defined my problem at the start, the more concrete are the answers I get at the end. If I am focusing on compositions with multiple elements, I know to sketch down the paintings or collages I see where many things are arranged into a coherent whole. How does the scale of the largest pieces in the composition compare to the smaller ones? Does the physical size of the artwork matter? How can I compare that to my interface?

I’ve learned from experience to review my notes before I leave a museum. I lose a lot if I leave and have dinner right after, and then try to remember my impressions from the museum. In the quick notes, I try to keep separate the things I observed and the solutions I want to try out.

5: Imagine!

Sometimes, I go through the exercise of “translating” the art I am seeing into another medium. How would this painting or sculpture look as a website? (What would my UX design problem look like as a painting?)

6: Re-define the problem

Sometimes the best outcome of a museum trip (or a walk) is not a specific solution to that problem I was stuck on, but rather a realization that I’ve been thinking about it in the wrong way to begin with. Perhaps, the problem was not how to arrange a complex set of elements, but the need to have them all in one place. I could solve it by deciding to reduce complexity and only present a smaller set at the same time. Getting out and changing my environment often kick-starts a process of “bigger” thinking and lets me make better work going forward.

There are four different types of flowers in a single painting: the geraniums in the pot, the dry flower on the table (above!), the flowers painted on the plate, and the ones on the wallpaper. I love looking at details.

Why a museum is good for switching context

Museums do two things very well for me: allow me to think bigger, and allow me to think different.

Bigger:

Design, especially when I’m working on a large or complex project, can get me super focused. This mode is great for figuring out details, but it can be deceiving. I can start feeling like the problem I’m working on is large, universal, and difficult, while it is in fact a special case within a special case. An art exhibition helps me realize that other ways of thinking exist, and that there are many bigger problems that surround the space for which I am building a solution.

Different:

Focusing on a different genre of work can clear out the habitual ways in which I think about design. Looking at paintings, drawings, sculpture or tapestries is related enough to my work, but at the same time far enough removed that I can relax without losing context altogether.

In addition to museums - walking in nature, even without art to focus on, is a popular creative tool. The illustrator Maira Kalman takes purposeful walks in New York, and Julia Cameron recommends daily walks in her best-selling The Artist’s Way - keep digging and you’ll find many more examples.

So - getting out of my workspace and into a museum is great for thinking bigger, and for thinking differently.

Things to try

Look at the art twice

I often do a quick tour of all the galleries, then chose a few that caught my attention so I can focus on them. It can be revealing to look at the art twice: first, intentionally out of context, and then a second time after reading the introductory essay and the works’ descriptions. I like to think my own work is clear, but looking at art and seeing exactly how much of the meaning may not be evident from a quick look is a great exercise in self awareness. Is my work just as easy to misinterpret?

The first idea might not be relevant

And this is okay. Don’t be afraid if the first associations and solutions have nothing to do with the problem you’re stuck on. Write them down and move on. If you’re like me, you’ll have ten different ideas, and maybe one of them will be relevant to the objective you’ve set.

Document, then quickly move on

If you don’t capture the ideas by sketching or writing them down, they will continue rolling around in your head. I know because this always happens to me when I take long solo walks just to think. I end up curling a finger for each idea or point I want to remember, and making a mental list (like “five things, in order, that I thought about trying today”). When I come back from the walk, I know I need to recall five things. Having them in order helps me remember what they were.

But it would be much easier to quickly write or sketch the ideas as I get them! Otherwise thy are keeping a part of my brain busy, and less of my energy can go toward making new ones, or solving the problem I’m stuck on.

Keep good notes for later

I often come back to my photos, notes and sketches from exhibitions I’ve seen over the years. I’ve put more work into taking the notes and photos as I’ve realized their value. I do wish they were better organized, but even accidentally stumbling upon a sketchbook I forgot I had from years ago can help me remember my state of mind and the ideas I gathered from art I’ve seen back then.

A sketchbook can be messy, and that’s ok. It’s a sketchbook! At any drawing skill level, I’ve found that a combination of text and image works better than written notes alone. Even a quickly sketched picture will help me remember what I was thinking much quicker and more vividly than reading a full page of notes.

Photos are great as well. I have access to professional photo equipment when I need it, but even the phone camera can do a great job. Again, my best photo notes are a combination of text and image. When I really care about a collection of photos, I take time to write out something like a blog post (not that I’ll necessarily publish it) and caption each photo with what I liked or noticed in it, and how it relates to the theme of the post. This way, I both gain clarity about what I’ve seen, and remember it for a longer time. I can always come back to those notes and quickly integrate the ideas into a new project.

Look at old notes

A quick dig through old sketches and notes can be almost as good as going to a new show. My notes (sometimes, years later) help me re-examine my own thinking and see whether anything has changed. I re-discover ideas I had long ago forgotten, and attack them with fresh skills and perspective (or, sometimes, realize how silly they were!)

Most importantly, with some time between the person I was then and the person I am now, it’s much easier to sort and prioritize ideas I might want to make into actual things. All fresh ideas seem ingenious precisely because they’re fresh. It’s tough to schedule and prioritize in that situation. But if an idea holds up even after a few months, I know I have no choice but to make something of it.

The practical bits

What if there’s no museum near me?

I am very lucky in that I’ve always lived in cities with plenty of access to art. But in addition to going to the top art museums, I’ve also made an effort to seek out the art that’s a little bit out of the way. Consider these:

- Every college and university will likely have a gallery. There might be special exhibitions, but also a less-promoted permanent collection somewhere on campus.

- Look for public art. Montreal was a great example, the public spaces downtown will have art most of the time, and the installations changed several times a year.

- Non-art museums are just as good as art if you want to switch context and get out of a rut.

- Open studios are an annual or semi-annual event when artists who might not have a permanent gallery space show their work where it’s made. These events often happen in the fall to allow for holiday related shopping, and after any summer fairs and festivals that the artists would take part in have finished.

- Year-end shows at schools can have a great variety in fresh work. My favorite, which I make time to visit every year, is the Yale University Graduate School of Design year-end show.

What if it’s no good?

Very rarely, it happens: I find a museum or an art show that could have been done much better. Even in this case, not all is lost. I enjoy seeing the contrast in quality once in a while, and I get a kick out of listing all of the potential aesthetic and just plain usability improvements I would make if given he chance. Even this can help me get back on track and nudge me toward finishing that thing I was stuck on.

So…?

Make time to go and see art. See it purposefully. For a designer, there is almost no excuse not to. It won’t just help you get unstuck on a current project. It will fuel your thinking for the work you are about to do.