Diagilev’s Ballets Russes, Magic and Design

Serge Diaghilev was a Russian aristocrat with an insatiable interest in the arts. His enthusiasm and hard work created the Ballets Russes - a strong influence in music, dance, the theatre, design, and even fashion to this day.

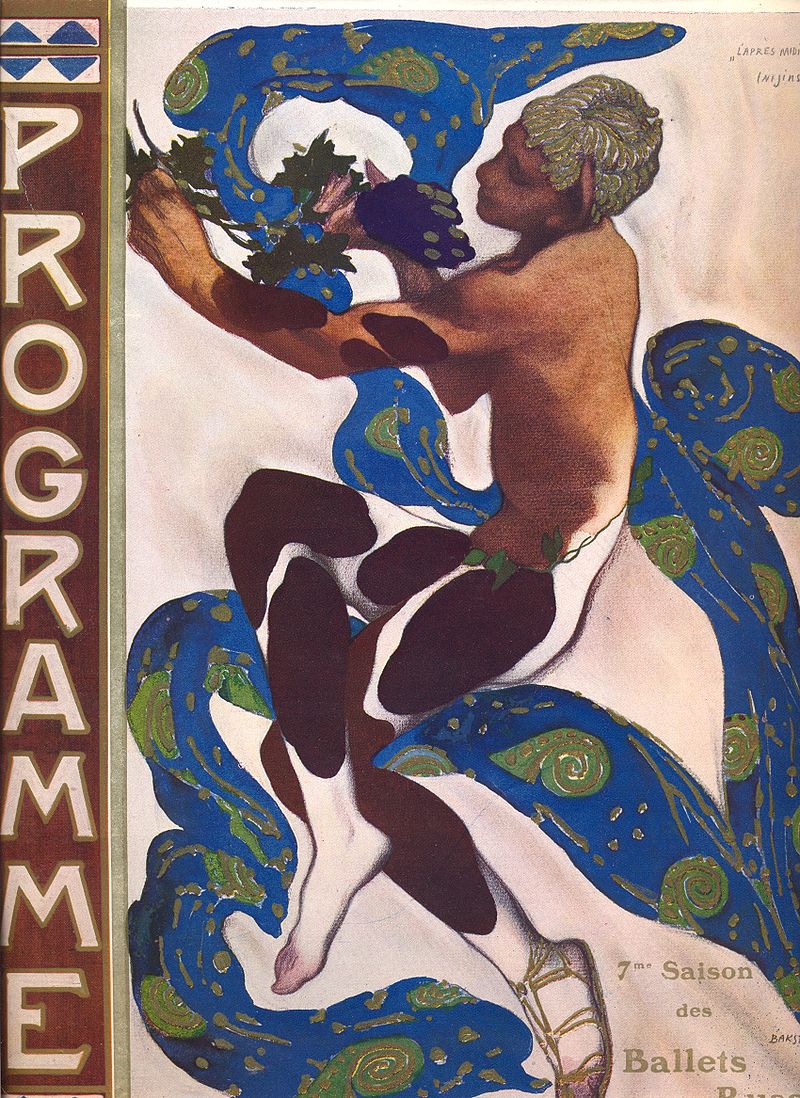

Poster for Afternoon of a Faun (1912)

I’ve always had an interest in theatre and ballet costuming. The designer can create something great out of materials that, but themselves, do not look quite as magical. The same fabrics that shine on stage can look faded, or even garish when seen by themselves. It’s every part of the production working together that makes the experience what it is. And it’s just like design.

When Diagilev originally decided to put together a ballet troupe, he did it for two reasons. One - he needed a way to combine his passion for painting and for music. He patronized both arts but wanted to make the works even stronger by putting the two mediums together. And the second reason - ballet was in a decline. There were few famous ballet companies doing popular work, but a steady demand for theatre and dance productions from the growing urban population in Europe.

Making the arts work together

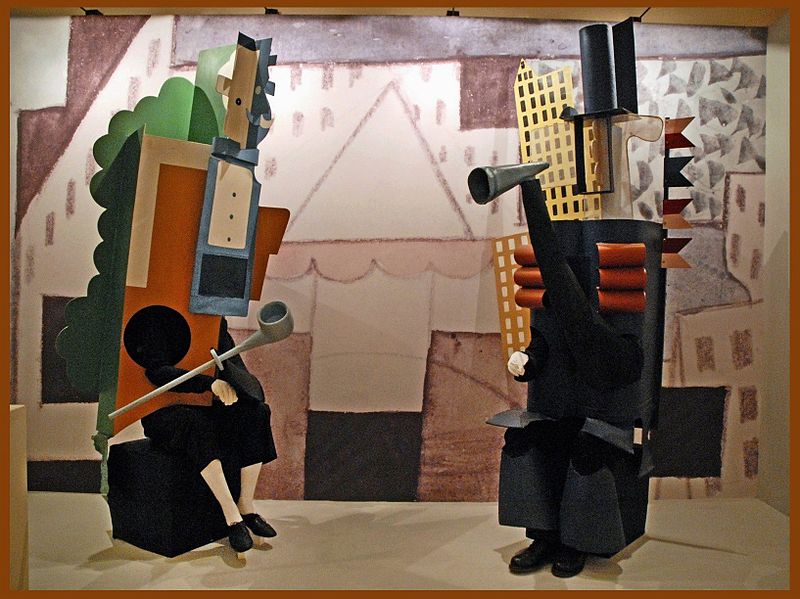

His avant grade approach to running a company was to make disciplines work together. Before Diaghilev, music scores, the set design and the costumes were rarely created together, to complement each other. Diaghilev commissioned new music, and used existing pieces from the best composers. He worked with artists like Natalia Goncharova (one of the leaders of the Russian avant-garde), Matisse and Picasso.

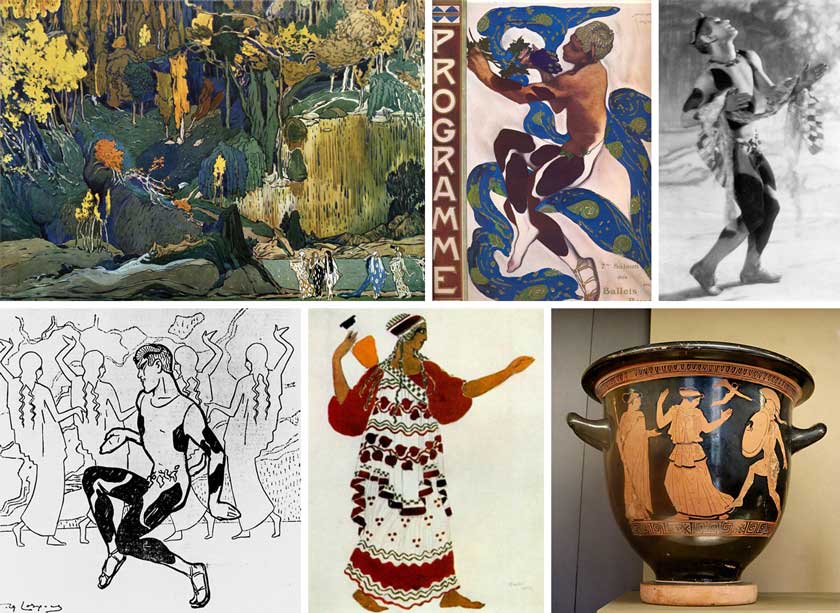

Afternoon of a Faun, like all Diaghilev projects, was a true coming together in one magical production. Photography was still a very new medium, but even then, the portraits of dancers in the troupe attempted to convey their dynamism and movement. The avant garde choreography drew references from Greek ceramics. Leon Bakst, a famous painter in his own right, worked on the costume sketches and stage design. Posters and printed programs were designed to the height of the Art Nouveau style. And it was the magic of all parts coming together in a unified whole that made the production so strong and, in turn, allowed each artist to shine in their own discipline.

Was there “design” in 1901?

In addition to making Russian culture wildly popular (if exotic) for the next several decades, I believe that Serge Diaghilev created the profession of experience design. Beginning in the early 1900s, before The Bauhaus even existed, he was designing multi-media presentations like no other.

Systems thinking, but in fashion

His legacy spreads far. In addition to revolutionizing ballet, he influenced fashion for years to come. (He even worked with Coco Chanel to create costumes for one of his ballets.) I feel that the theatrical presentations we see in the September Vogue, and every runway show, owe much to his vision.

Even when I read fashion advise to think about whole outfits rather than individual pieces of clothing - doesn’t it draw on a similar principle? It’s not one ingredient, but rather the sum of the parts.

What UX design can learn from theatre magic

Big and small

To make a large production work, Diagilev had to think big and small at the same time. He discussed minute details of costume-making with the tailors to ensure quality and dancers’ comfort. But then, he switched to “big picture” mode to have conversations with wealthy patrons about the grand vision he had for the company. I imagine he had to give Matisse and Picasso creative freedom to make their contributions, but still agree on the theoretical basis of the project.

Constraints

A traveling performance is not easy. The Ballets Russes travelled extensively and frequently had to adapt to challenging conditions. Stage dimensions, available equipment, even tailors were different. Working around challenges and constraints, while keeping the conceptual goals of a project in focus is very much design problem. But it’s working around constraints and towards an elegant solution of a problem that makes design worth it.

It’s not just the ingredients

In studying the Ballets Russes, I keep coming back to one thing. It’s not just the ingredients - it’s how they must come together and just work. The careful mix and the balance between different artists, disciplines and styles is what makes something good.

Set Design for "The Firebird" (1923)